by Will McMillan

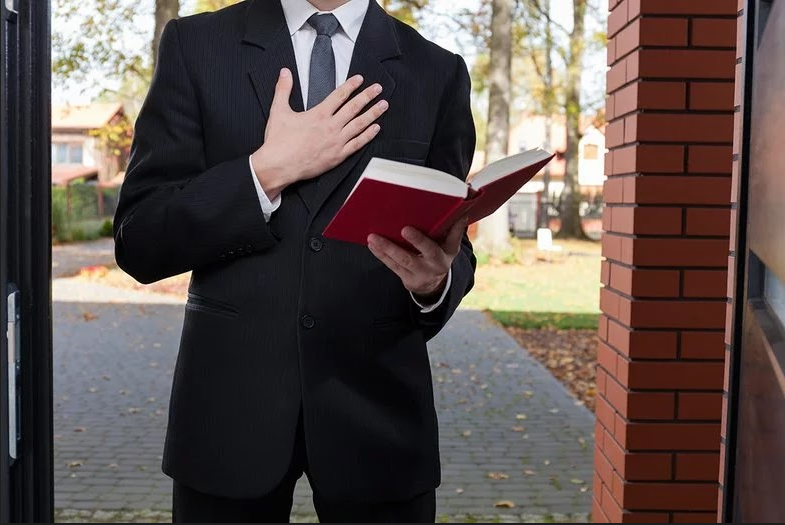

I hear screaming on the other side of the door. An epic showdown between a man and a woman. I can’t make out actual words; they’re shouting too fast, too loud, and too close to each other. Strikes of verbal lightning splitting the air, electric with the heat of their outrage. I want to do an about-face and sneak off their porch before they notice I’m there. But if I don’t knock, if I don’t get their attention, then these people will die. Come Armageddon, theirs will be a fiery, tormented, agonizing demise. And I will die along with them, made guilty by blood for not trying to save them.

I hear screaming on the other side of the door. An epic showdown between a man and a woman. I can’t make out actual words; they’re shouting too fast, too loud, and too close to each other. Strikes of verbal lightning splitting the air, electric with the heat of their outrage. I want to do an about-face and sneak off their porch before they notice I’m there. But if I don’t knock, if I don’t get their attention, then these people will die. Come Armageddon, theirs will be a fiery, tormented, agonizing demise. And I will die along with them, made guilty by blood for not trying to save them.

Folded in the back of the Bible I’m clutching is a note card with a vague description of the people beyond the door. Husband and wife. Refused literature. Next to that, in bold red marker, twice underlined, DNC. As Jehovah’s Witnesses, we have a handful of two- and three-letter abbreviations we use to describe the people we encounter out in the ministry, when we go door to door in our efforts to preach God’s word to the masses.

HBH: Home, But Hiding.

RV: Return Visit.

WTL: Woman, Took Literature.

The most formidable of all abbreviations, however, the one that instills the most fear in a Witness (or at least in me), is the dreaded DNC.

Do. Not. Call.

Any person graced with these letters has aggressively insisted that Witnesses never visit them again. Often with cursing. Sometimes with violence. A sister out in service once had a gun pulled on her by the man who opened the door to greet her. A brother had to make a fast getaway when a householder unleashed his trained attack dogs. Which is why you never work DNCs by yourself. Even if you’re alone at the door, as I am at this moment, there are at least three other people keeping tabs in the car. Once a year, usually in May, when we hope the warming spring weather will encourage householders to be kinder, any home that’s been recorded as DNC gets a follow-up visit.

“People’s situations can change,” the Elders remind us every year from the stage. “A person not willing to listen to God’s word this year might suddenly find that they are in the next. Or maybe the year after that. We just don’t know what’s in a person’s heart, brothers and sisters. The only one who knows is Jehovah. And we want to keep ourselves free of blood guilt.”

I always sit straighter when an Elder threatens us with blood guilt, understanding that if we don’t tell our neighbors, the world as it is will soon be destroyed, and we’re just as responsible for their certain destruction as they are. We’ll drown in their blood along with our own. It’s an apt metaphor, one that chains itself around the neck of my conscience, though Jesus insists that his burden is light. To be free of blood guilt, we must preach this good news for all the people to hear. Even the ones who aggressively insist they’ve heard us enough.

Many times the DNC isn’t home, so we’ll leave a small tract folded beside the doorknob. With Do Not Calls, it’s a one-and-done situation, so we won’t come again until the same time next year.

Sometimes, the DNC doesn’t know who we are. They’re usually older and take us at first for neighbors or well-dressed delivery men. Once, a man thought I was from the local charity group that came by twice a month to bring him his groceries. He opened his door with a smile and a wave, his silver hair sprouting from the sides of his head like matted steel wool. His slippers were the same shade of blue as his robe.

“Oh, no. I’m not from the Gleaners. I’m with a volunteer group stopping by to share a positive message from the Bible. Would you mind if I shared a scripture with you?”

Realization lit through his mind like fire through a hay field, and I watched as his features shifted from, dull, soft confusion into venomous outrage. His cloudy eyes became clear, narrowing into reptilian slits. “You people destroyed my marriage! Get your miserable ass off my porch now! Get out of here now!”

I was at least a head taller and two generations younger, but his fury bit hard. It was the sort that was rabid, and I scrambled away as he advanced from his door, his body shaking with tangible anger.

“Get out of here! Just get the hell out!”

The worst are the DNCs who used to be Witnesses. Who used to be a part of Jehovah’s organization, but have been disfellowshipped or have dissociated themselves from the rest of us Witnesses. They may not be violent or come out swinging a weapon, yet they’re deemed DNC-worthy because of the scope of their sin. For Witnesses, this could be either drug use or sex with the wrong person. Often, they bear no resemblance to their previous selves, having abandoned biblical teachings and Jehovah’s favor for premarital relations or worse, same-sex relations, and full arm tattoos. What we see as encouragement to return to the faith they interpret as shaming and bemused condescension. They may not threaten or swear or call us bad names, but a slammed door in your face makes a point just the same. That they once knew Jehovah, that they once had his favor and have chosen to leave it, all but assures their upcoming destruction. We walk away from their doors, shaking our heads, pitying the state of their well-hardened hearts.

“We just don’t know what’s in a person’s heart,” the Elders remind us. “The only one who knows is Jehovah.”

Standing in front of the door now, it’s my own heart I can’t help but think of. In particular, how it’s beating more with anxiety than blood, how it’s insisting I consider my surroundings. There are plants on the porch, but they’re dying. Spiders have spun webs on their frail, crumbling leaves. Stacks of newspapers, still in their slick, yellow wrapping, are piled in a heap beside the front door. Drowned cigarettes lie bloated and decayed in mason jars filled with murky rainwater. Nothing I see suggests these people have much use for visitors. And of course, there’s the screaming, which hasn’t let up since I got out of the car, since I walked on the sidewalk that leads to this house, since I made my way up the cracked, wooden steps to this porch. The screaming. That more than anything suggests what sort of reception I’m in for.

Caught in an ambush of dead spiders and deadly anger, I get the sensation I’m being observed. I feel eyes on me, watching my movements, evaluating my actions. But I don’t feel them from inside of the house. I feel them from the car on the street, from the Witnesses who’re sitting inside it, watching to see if anyone comes to the door, watching my reaction, in case somebody does.

For truly I say to you, if you have faith the size of a mustard grain… I pray to myself, lifting my hand to knock. It’s my standard prayer every time my faith starts to waver. My lifeline to God.

You will say to this mountain, ‘”move from here to there…'” There’s a metal screen door, flimsy and filthy, in front of the wood door behind it. If I open it to knock, the polite thing to do, the screen door will rattle, will squeak. Screaming or not, they’ll know that I’m here.

“And it will move, and nothing will be impossible for you.”

I ball up my fist and rap on the door with my knuckles. Five solid taps. At least, I hope that’s what it looks like. The group in the car, with their windows rolled up, can see but not hear me. My knuckles barely touch the front door. Only inches away and I can barely hear my skin petting the flaked, battered wood. A butterfly landing would make more of a racket. No one inside the house could have heard me, even if it were utterly silent. I wait a few moments, then do it again, putting on a production in case anyone from the car is observing. Another few seconds and I pull a tract from inside my suit jacket. Folding it fast in my fingers, I slip it between the door and the door frame. Carefully, quickly, I turn and make my way off their porch, gulping sweet pulls of air as the sounds of aggression drift away and behind me.

“No one came to the door,” I say to the group. I buckle myself into my seat, smoothing my tie, my pants, my jacket. “They were too busy fighting to care about me. I guess we’ll try again next year.”

Behind the steering wheel, the Elder nods with solemn approval. “Brother, you did all you could. Jehovah always blesses our efforts.”

As it dries and begins to atomize in the air, the sweat on my skin transforms into guilt. I breathe it in deep as we pull away from the house. No one in the car knows what I’ve done. But Jehovah, he knows. He was watching me too, saw the fake-out I pulled. And I can’t help but envision a series of events that I’ve set into motion.

Armageddon has come. Jehovah is bringing an end to this world, and all the evil that’s thriving within it. He’s destroying the Murderers. He’s destroying the Idolaters, the Sorcerers, the Liars. And when he begins to destroy the Cowards, he pauses to take special consideration of me, allowing me to see the husband and wife that once, long ago, I had a chance to speak out to. He allows me to hear their outcries as the world all around them comes to an end, as they face their own impending destruction.

“Why didn’t you actually knock?! Why did you only pretend? We were shouting, we know, but we would have listened! We would have heard what you said and turned toward Jehovah, but we couldn’t hear you at all! Why didn’t you save us?! Why didn’t you try?!”

But of course, I can’t answer, because they’re already judged, they’re already dead. And because my blood is now guilty, I’m already dead too.

I close my eyes as we pull away from the house, making a silent deal with Jehovah. Next year, I promise. I’ll come by their house this time next year. And no matter what, I promise I’ll knock. No matter how scared, no matter how nervous. I promise I’ll stand there and take whatever they might want to say. Just don’t be mad. Just don’t destroy me. I promise next time that I’ll knock. I promise. I promise…

Another year comes. Another year goes. And another year comes and goes after that. The years collect and pile up on themselves like dead leaves or rotting newspapers, and I never make my way back to that sagging front porch, never attempt to knock on that door.

![]()

The years continue to slide out beneath me, four years, then five, and then six, until one year I find that I’m no longer a Witness, no longer a part of Jehovah’s organization. What I am instead is disfellowshipped, formerly closeted and recently out, with a tattoo on my back and full facial hair. I’m the kind of person I used to look at and wonder which scriptures might turn them around, turn them away from their sinning and back to Jehovah. What I am is a name written down on a card, three letters scribbled next to my name, someone who receives a visit from Witnesses just once every year, most likely in May, when the weather is warmer. And still the years continue to slide, one year disfellowshipped, and then another, and another. Each year bringing a spring along with it, bringing sunlight spilling in through my windows. So many springs and not a peep at my door. And then, one year brings a warm Sunday morning, and wandering into my living room, just for a moment, I think I hear something outside my front door. Something a bit like a knock, like someone tapping their fingers as lightly as possible. Someone padding their knuckles on my door frame perhaps, too nervous to speak to a former believer to make any real noise.

I stop moving at once, a familiar anxiety blooming throughout my body. My heartbeat does its best to consume this anxiety, ratcheting up its beat. Yes indeed, I remember this feeling. I remember this heartbeat. I stop what I’m doing, sunlight around me, unsure what I’ll do if the tapping I hear, the light touch of fingers, transforms into a sound I can’t mistake, a sound that can only be somebody knocking.

I keep myself still. My hands have balled up into cold, sweaty fists. Out the window I see a car on the street. Was it always parked there?

I wait. I fear. I listen.

I wonder what my front porch looks like, what sort of hints it might be whispering about the person beyond the front door, about me.

I wonder if someone’s out there, holding still from the terror, imploring Jehovah through scriptures, through panic.

I wonder whose heart they’re hoping to turn. Whose life they’re wanting to rescue. Whose blood they’re hoping to set free from guilt.

Mine?

Or their own?

Will McMillan lives and writes in Portland, Oregon. His work has appeared in literary journals including The Sun, Redivider, Hippocampus, and Pidgeonholed. Will has also been interviewed on This American Life, in an episode based on an essay he published in Nailed. Find him at https://www.willjmcmillan.com.

Photographer unknown