by Oormila Vijayakrishnan Prahlad

Curdled Chopin

Freshly dehusked from

plaster of paris,

my right hand savours

the wash of sun

after eight constricted weeks.

Gnarled phalanges ache

as healed hairline fractures

feel the pull of

new links knitted within

the matrices of my bones.

My good hand booms a string

of broken chords, a sprinkling

of ebony tones,

waiting in anticipation

as my twig of a right hand

gingerly feels the cold keys

for the first time in months.

A timid staccato, then

Rubato—my fingers tango

to a slow but steady start.

Wasted muscles groan,

smudged notes

rise and fall.

It’s a cacophony

of curdled Chopin

that fills the living room.

![]()

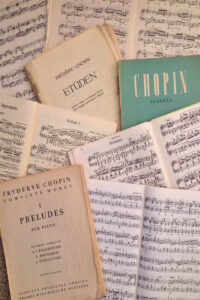

Muscle Memory

Years later, when I book

a curbside collection

for the broken oven,

the radiators and fly screens

piled in the garage, I find

the cardboard box with

the sheaf of piano scores

she had wanted me to inherit.

Her three sons had shunned

their mother’s instrument

and even though there were

prodigies aplenty who

made her proud, she chose me

with my unlikely background,

with no musicality

in my family tree,

the student who laboured over

all performance pieces,

to receive her dearest possession.

I can’t bear to look at this

relic from my past when I

can barely play a shred

of this sublime music now.

They might as well be

peppercorns, I scoff—

these semiquavers

spattered in clumps across

the linen-grey sheets.

I grudgingly trace the

impossible highways

of arpeggios, the gullies

of diminuendos

with an ache

metastasizing in my heart.

But I want to believe

I can lift them again the way

she used to, give them effortless

flight, so I take the box

inside, and attempt to

clean the cobwebs off

both paper and mind

as the preludes and fugues

rustle at me from within

her treasured

Well-Tempered Clavier.

And I tease the keys, starting

and stopping, decoding

one bar at a time

like stringing together

a clump of elusive beads and

it isn’t long before

I’m caught in flashbacks

of a self, long withered—

the spotlight crowning my waves,

back arched,

fingers curled—

fifteen,

fearless.

![]()

A friend asks for advice on which piano to buy

for his teen who has suddenly retreated

into a shell, and I promptly scan

listings for second-hands and promise

to make phone calls. He hopes that

along with the therapy and medication,

music will restore his child, and

the piano lessons he has enrolled

her in will lead her out

of the fog. I tell him it’s

a great idea.

I revisit a phase from my younger days

when my own mind

was patched together with

regular pumps of Prozac—my mouth

perpetually dry, a tremor

disrupting my brush

as I painted the scarlet blooms

of the flame of the forest near

the railway lines. Those days,

with my instrument stranded in

a different country, I pined

for Saturdays, when a stolen hour at

a pianist friend’s place, to play

the fragments of pieces I still

remembered, was my thin escape

from the voices

thrumming in my head.

It’s evening and he messages again:

Will this help her? Will she be herself

again? I sigh and bite my lip,

texting back that I’ve found

a Baldwin in the neighbourhood,

great sounding, reasonable condition,

free to a good home. Then I add

a heart emoji after

my most reassuring cliches—

Things will get better,

One day at a time.

Oormila Vijayakrishnan Prahlad is an Indian-Australian artist, poet, and pianist who lives and works in Sydney on the land of the Ku-ring-gai people of the Eora Nation. A member of Sydney’s North Shore Poetry Project, Oormila is a chief editor for Authora Australis. Recent poems have been featured in Tistelblomma, Silver Birch Press, and Underwood Press, and Oormila’s recent artwork has appeared in The Amsterdam Quarterly, Back Patio Press, and on the covers of Pithead Chapel, Ang(st) the body zine. Find her @oormilaprahlad and www.instagram.com/oormila_paintings

Photo by unknown photographer