By Elizabeth Peavey

“Your mother and I have been talking.”

These are words no one ever wants to hear, especially not an aimless, twenty-four-year-old would-be poetess. I’d just driven the 40 minutes from Portland to my parents’ house in Bath to do laundry and raid the liquor cabinet. And maybe get in a round of golf with my dad, if I could pry him away from his relentless yardwork.

I’d found him out back messing with the mower, cleaning the blade caked with wet grass. He didn’t look at me as he spoke. “I’ve made an appointment for you with Al Ferguson at the Credit Union to talk about getting your foot in the door. It’s time you settle down and get a job.”

Now wait a minute. This was Mom’s territory. She was the one who nagged. She was the one who constantly told me to do something with my hair, and by that she hadn’t meant the bright-pink spiky shag I was currently sporting. She was the one who kept trying to get me to dress “nicer.” Every birthday and Christmas I silently groaned as I pulled back the wrapping on the shiny red Talbots boxes, as I’m sure she groaned as she went to her desk for the receipts.

But Dad? My daddy was my pal, my golf and boating buddy. The one who taught me to drive a stick and fix a flat. To play poker, to do crosswords, and to say things like, “Are you impugning my veracity?” He was the fun one.

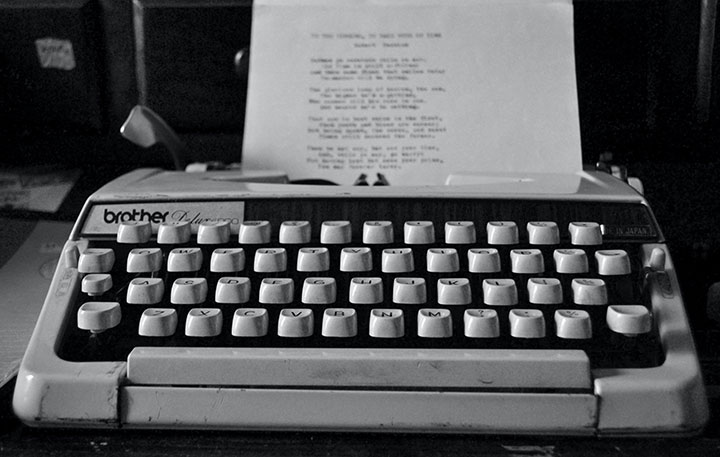

“I have a job,” I whined. He glanced up at me. Okay, so waiting tables by night and writing by day was not exactly the secure career path he had in mind. But I was an artist. It didn’t matter to me what I did to support my craft. Since high school I’d already amassed quite a work history: information-booth clerk, lawn mower, bellhop, night watchman, hat-check girl. The avalanche of restaurant and retail work that followed. But mostly I’d bummed around: a semester in London; then off to “do” Europe; followed by a 13,000-mile, solo cross-country trek in my trusty rusty Subaru. Now I was back home and broke again, living with two gay men friends, working odd jobs, and plugging away at the crappy play I started writing in college.

What could possibly be the problem?

My father went into sales mode. He explained how great a life in the Credit Union would be for me. While he spent his career as an upper-level civilian at the Brunswick Naval Air Station—a job he hated and couldn’t retire from fast enough—he had for years served on the board of the Maine Credit Union League and its insurance trust. There were all those perks: travel, meals, hotels, free key chains and potholders—all on the League. Dad highlighted these things, adding, “With our connections, you could practically write your own ticket.”

I felt sabotaged. I know it wasn’t that my father didn’t believe I could be a writer. My daddy was a one-woman feminist. He thought I could do anything. But he also was a child of the Depression. His father was a barber and his mother took in laundry and baked bread. They moved around a lot, supporting various family members. He wanted me to have a future that was stable. Safe. With lots of free stuff.

But I wasn’t going to be trapped in a job I hated, like he was. Or like those men in my hometown who streamed in and out of Bath Iron Works day after day, year after year, swinging their metal lunch pails, obeying the report of the whistle that echoed across town, calling them to work and releasing them at day’s end to trod home to their dull wives and dull 5 p.m. suppers. Not me! Never! I had dreams.

“I can’t,” I said. “I can’t work for the Credit Union. I’m going to be a writer.”

This was the first real disagreement we’d ever had. I know he was disappointed, but he said nothing. The blade was clear. He flipped the mower back over, gave a tug on the cord, and in a roar of exhaust and spraying grass, took off down the side of the house. A year later, he’d be dead of a heart attack.

I’ve been thinking of this moment a lot recently, as I find myself at the age of 61 without work, without a permanent living situation, and with no idea how to rebuild my hard-won career as a writer, speaker, and educator that in a matter of two days in March was reduced to rubble. Pandemic aside, I largely put myself here. I was the one who took the difficult career path. I was the one who left my perfectly lovely home and marriage two years ago. I was the one who always felt I had to reach for more.

What if I had chosen differently and taken the interview? I know I wouldn’t be in this spot. I’m sure Dad was right. I would’ve risen through the ranks of the Credit Union. Maybe been a figure on the national scene. I’d probably even be retired by now. Maybe sitting on my boat. Well I doubt that, but certainly not watching my federal unemployment run out and packing my things yet again to move from one temporary lodging to another while I try to figure out next steps.

My dad never got to see any other adult version of me beyond the reckless, snotty punk too good for a day job. Didn’t see the tenacity and courage it took to pursue a career filled with no’s and rejections. Never saw the articles and books eventually published. The awards won. The years of standing ovations at my one-woman show. The travel, the accolades, and, yes, the perks—not to mention a shopping bag filled with name tags that read: Elizabeth Peavey, Author.

Parents always worry about how their kids will fare. The next generation is supposed to do “better” than the last. Make more, have more, do more. I wonder if, as he lay dying, that was a last concern for my dad. How was his little girl going to make her way in the world without him—or the Credit Union? If I could’ve told him one thing, it would’ve been this:

It’s OK, Daddy. I have a job, my first job, and my forever job. I’m a writer, and that’s better than anything I could have imagined. I’m going to be fine.

Elizabeth Peavey is the author of three books and countless print columns and features, including for Down East magazine, where she is a contributing editor. Her one-woman show, My Mother’s Clothes Are Not My Mother, played to sold-out houses for six years and received the Maine Literary Award for Best Drama. She was a lecturer of public speaking at the University of Southern Maine for over 20 years and has taught memoir writing since the days of quill and parchment. She is a frequent keynote and guest lecturer at conferences and schools.

Photo by jules a.