By Victoria Morsell

Our mother was getting married to a guy in Chino, and we had no idea what to wear. My sisters, fraternal twins, were seniors in high school. I was eighteen months younger and secretly wanted to be the kind of girl who could throw on a cute dress and call it a day. But then puberty hijacked my body. By the time I was fifteen I’d gained twenty pounds, with a good portion of that in my boobs. No little dresses for me. I settled on a pair of stiff jeans, a high-necked velour sweatshirt shapeless enough to neutralize my breasts, and chunky orange leather shoes for my extra-wide feet.

My sisters tried on different combinations, dashing back and forth from their bedrooms to the full-length mirror in the hall. Kari chose a bright striped shirt and Dittos. Jennifer landed on a cream-colored sweater and jeans with her white Candie’s sandals, even though it was January. We never wore high heels or makeup or carried purses. We hadn’t even worked up the courage to ask for bras until our fully formed breasts were flopping around, getting unwanted attention from men. Maybe we didn’t want our mom to think we’d become too grown up for her, our transformation into adulthood a kind of betrayal.

“I like my outfit,” said Jennifer. “I look solid.”

“Solid” meant cute and effortless. Solid was everything.

I did not look solid.

I found Mom in the kitchen with a cigarette pinched between her teeth, scrunching her short blonde hair into curls over the steaming kettle. She’d been up since dawn and was already dressed. My sisters and I bumped around the small kitchen, tired and cranky, fixing toast and Instant Breakfast, as we all waited for Diane to arrive. Outside our corner tract house in Ventura, fog tumbled in from the ocean, drifting between the slats of our useless squat fence. Dogs were always escaping over it and strangers could easily gaze into our windows and tiny backyard.

Mom was pacing, opening the front door and then slamming it shut with a big sigh. Diane, her friend from law school, tended to start drinking early in the day.

“Don’t worry,” I said, stirring powdered chocolate into my milk. “She’ll be here.”

Even though I did worry. I worried about everything, especially my mom. Her moods bounced around from upbeat to angry, to sobbing on the couch or hiding away in her room. I’d lie awake at night and say my little agnostic prayers, asking for someone or something up there to protect her. Knowing all the while it would be up to me to make her happy and keep her safe.

Diane eventually showed up, wobbling through the door in her usual state. Her legs were pale and bruised, hair tangled, lipstick smudged. She looked like she’d been tossed from a speeding car. I could see that she’d tried to pull it together with high heels and a silky chiffon dress, but the dress was too short and tight across her belly, and the spaghetti straps kept sliding off her shoulders. It made me sad to look at her. I’d seen, in photos, how beautiful she once was.

“Fuck it,” Diane slurred, her foot slipping as she hoisted herself into the front seat of our VW bus. She lit a cigarette, so did my mom, and off we went, Lynyrd Skynyrd blasting from the front seat. It was 1980 and the band’s lead singer had died in a plane crash three years before, but Mom and Diane still played their music over and over.

We had two and a half hours to go before we’d arrive at the California Institute for Men in Chino. My mom was about to marry her former client, but all I could think about was my hideous outfit. I wanted to hide and eat. I had zero desire to see John. Mom’s future “husband” was a stranger, a convict, twelve years younger than her. My sisters and I had met him only once, at an outdoor prison picnic. We barely spoke. He was too busy making out with my mom under a tree, his hands all over her body, probably extracting the balloons of pot she’d smuggled in.

Over the past six months or so, there had been daily collect calls. Sometimes I’d answer and we’d try to make awkward small talk. He’d call me kiddo and ask me about school without really listening. I’d quickly hand him off to my mom. I saw the way she waited for that phone to ring. The way those conversations could make her giddy or send her spiraling into depression. And now she was marrying him. Why? The guy was always asking for something: money for the commissary or cigarettes or a new Walkman. If she asked him what he did with the last Walkman she bought, he’d claim he had to use it as a pay-off or some inmate would kill him. I was only sixteen and I’d never had a boyfriend, but I saw how Mom needed to believe his stories in order to believe in herself. As a lawyer, her job was to defend, not judge. She saw things in her clients that other people didn’t. She saw their humanity and potential. Most of them, she told us, had been victims of abuse and neglect.

But I still didn’t trust John.

Finally, we were there. We pulled into the prison parking lot while Diane whipped out a bottle of champagne to start the celebration.

“Not here!” Mom stopped her. “You can’t drink champagne in a prison parking lot.”

Suddenly she was hyper-responsible, one of those confusing moments when her ethics kicked in. Mom was a contradiction: either driving with a beer between her knees or wagging a disapproving finger over Diane’s parking lot champagne. Either smuggling pot to her boyfriend in prison or going back to a store because the cashier gave her too much change.

“Don’t forget the rings,” she said to Diane. Of course, Mom had to buy both wedding rings. She’d had to buy both rings when she married my dad, too. But at least he was a nuclear physicist, not a felon.

Diane covered her mouth and gasped. “What rings?” She laughed and patted her purse. “Just kidding. Got ’em right here.”

Mom went in ahead of us to take care of paperwork and speak to the prison chaplain. The California Institute for Men in Chino was a minimum-security prison; as an attorney, she must have had special privileges there. Or maybe they gave her a hard time. Maybe they didn’t like her type: pretty female lawyer hooking up with her cocky young client. Before coming there, John had been doing time in Soledad for burglary. He’d had plenty of priors—mostly burglaries, a stolen gun. Later he would advance to armed robberies.

The story my mom told me was that John saved the life of a Black inmate in Soledad and the Aryan Brotherhood wasn’t happy about it. John’s only salvation was to leave an anonymous “kite,” prison slang for a contraband note passed between inmates. The kite said, “John S. has a knife on him.” The guards searched his room, found the knife, and pulled him out. John explained that he’d planted the knife on himself to get away from the Brotherhood. Somehow, they believed his story, and my mom did, too. She was able to get him transferred to CRC and into the Chino dive program. The program was physically rigorous, with an eighty percent dropout rate. But if John could stick it out, he would be trained as a deep-sea diver and given a leg up in life. Jobs working on oil platforms paid divers more than a hundred thousand a year, an amazing opportunity for an ex-con.

My sisters and I waited in the van with Diane, who couldn’t resist opening the champagne for a little chug before it was time to go. After wrestling with the cork, she gave up and left the open bottle on the floor of the car. Then, when it was time, the four of us walked the narrow pathway toward the chapel, past a chain link fence topped with loops of razor wire, below the cinder block building with barred windows.

Kari and Jennifer and I huddled together, our bodies tense, trying not to look up. Inmates peered down at us, gawking, grinning. Diane walked the concrete like a red carpet. I felt naked and jiggly, enormous in my big shoes. Inmates whistled and whooped and made kissing noises. Diane called right back to them in her raspy, up-all-night voice. “Keep dreaming, boys. You wish.”

The chapel was a windowless room with high ceilings. Mom stood near the pulpit, to the left of the chaplain, looking young and pretty in her blue wrap dress. An enormous wooden cross was mounted on the wall behind them. She smiled and waved when she saw us come in. My sisters and I slipped into the middle row and sat down on cold metal folding chairs. We were the only guests. Diane clacked up the aisle, struggling to walk straight, her hemline swinging. She took her place next to my mom, who nudged her, rolling her eyes up at the looming cross. They giggled like teenagers.

I just wanted to be alone somewhere with a jumbo bag of M&Ms.

Finally, John and his two groomsmen were led in by a couple of guards. We turned to look. They all moved down the aisle the same way, with a slow and loaded gait. John was tall, tan, and charismatic. He had a handlebar mustache and wore his long blond hair in a ponytail. The groomsmen wore flashy polyester button-up shirts and sported the same handlebar mustaches as John. In a few years both would be dead, killed in separate robberies. But that day they stood snickering next to John, elbowing each other, thrilled by the disruption in their prison routine.

Mom pointed us out to John, and he waved at us. It was a strange menagerie assembled at the prison pulpit: John with his hands clasped behind his back, smiling like a cat with a bird twitching in its mouth, Diane laughing like a harbor seal as she tottered on her little heels, and the two hulking groomsmen with crocodile grins. Then there was my mom, a former debutante from Boston, somehow perfectly at home.

The chaplain took a step forward.

“I’m so nervous!” Mom laughed.

The chaplain said, “It’s refreshing to have a nice, normal family for a change.”

“Who’s normal?” barked Diane.

The wedding vows were short and to the point. Rings were exchanged, then the kiss came. A big sloppy tongue kiss. John practically swallowed up my tiny mom. And it was done.

I sank down in my chair, dreading the next part when I would have to go up and say hello to my new stepdad. When he would introduce me to his creepy groomsmen. When John would look at me and right through me with those grey devil-eyes. At least Mom would be going home with us. The conjugal visit was four months away, so we didn’t have to think about it. Later, Mom would describe John’s tattoos, how one of them was her name, Mari, inked between his shoulder blades above a naked lady on horseback. The horse’s mane, blowing wildly over the letters, made “Mari” look like “Maris.” Was the buxom cartoon lady supposed to be my mom?

Mom motioned us over and we crowded together on the pulpit for a Polaroid photo. Then John turned to us, arms out. “Hey kiddos,” he said, and stepped closer for a hug. But the prison was on a tight schedule, and we were quickly whisked away. The clock was ticking. The groomsmen were about to turn back into mice, our VW bus back into a pumpkin. John was collected by guards and ushered to his cell. And I was spared.

In the parking lot, Diane lunged for the champagne. Mom scolded her and made her stick it in the trunk. As we headed home, my mom seemed antsy, preoccupied. I was, too. It was strange to think of her as a married woman again. Before we got on the freeway, she pulled the bus over and told Diane, “I’m ready for that champagne now.”

They drank from paper cups, smoked cigarettes, and listened to Linda Ronstadt sing about weed, whites, and wine over and over. My sisters and I played “I Spy.” Mom looked happy and I felt a weight lift slowly from my body. I’d always been good at pretending nothing weird was going on. Of squeezing strange occurrences into the category of routine. So I did what I always did and pushed the worry aside. Maybe John wasn’t so bad. Maybe our little family would be fine.

When we finally got home and Diane left, Mom went right to her room. She’d wilted a little. I wondered if she had regrets. I lay in bed that night and said my little prayers again—to whom or what, I didn’t know. Please let this marriage work.

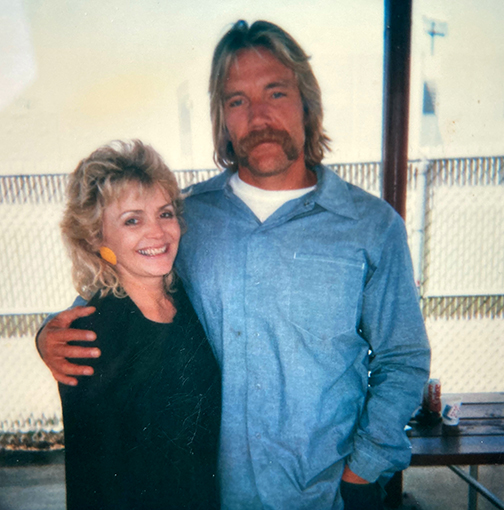

40 years later, I think of the photo we took on that pulpit. Our odd little grouping: John and his groomsmen with their heads tilted back, chests puffed out like tough guys. Mom and Diane smiling brightly. I’m standing next to them, awkward and shapeless in my stiff jeans, my face a blank. Looking closer, though, I can see doubt in my eyes while my hands, clasped tightly together, are trying to hold on to hope.

There are no photos of what later extinguished that hope: John forging checks, my mother almost dying of an overdose, her career nearly destroyed. And yet in that faded Polaroid I can see the strength in my hands. A power that eventually would pull me out of hiding and help me find the bold girl inside myself. If I could tell the worried teenager in the photo anything at all, I would tell her this: Don’t worry. While you’ll never stop hoping for your mother, a time will come when you start hoping—and caring—for yourself.

And you’ll know exactly what to wear when you go out into the world.

Victoria Morsell is a former actor living in Los Angeles and a graduate of Antioch University’s MFA program. She’s the winner of The 2021 Book Pipeline Unpublished Novel Contest and has been published in Santa Monica Review and Shondaland. Find Victoria on Instagram: @toriburd (Victoria Morsell Hemingson) and on twitter: @v_morsell.

Photo courtesy of author