Quick Work No. 5

Here, in micro-flash nonfiction, writers make quick work of compelling stories. During July 2020, we present short takes on work and working.

The Boys Department

by Michele Wick

After Grandpa died, Grandma became a sales lady at Alexander’s Department Store. At 70 years old, she had her first job. Grandpa never let Grandma work outside the home, although he’d let her play poker for rent money.

At Alexander’s, they believed Grandma was 55, and offered her a buyer’s job. But my elegant, five-foot tall Polish grandmother preferred the boys department, where she worked for 25 years.

On my wedding day, Grandma told me that I had nice “bubbies.” She also said that I could accomplish anything.

Sometimes, I forget this, and her, until I remember and press on.

Managed Care

by Gerard Sarnat

I wanted to make a difference. As an MD-CEO, my idea was to run that new health plan so members would get value for their hard-earned bucks. But the Board did not distinguish between providing care and inventorying boxes of Kleenex.

When someone instructed staff on how to manage customer expectations, I wondered, weren’t they patients anymore?

I learned that appeals were shamelessly disappeared, never to be ruled upon. My naïve ideals were disappeared too.

Our worthiness had quickly deteriorated.

I quit and went back to being a physician.

Pine Ridge Reservation, 1999

by Wren Bellavance-Grace

“Give these to the needy,” the note demands.

Not this one, I think, discarding the coat with a gerrymandered-county-shaped stain.

I expected Volunteer Vacation to be sweaty, grueling, heavy work. Instead: “Sort donations in the attic.” Sweaty? Definitely. Useful? We’ll see.

Scores of boxes—dog-eared books, chipped mugs, clueless INDIANS jerseys. And some useful things. I map out the newly organized attic, but nobody cares. It gets reorganized every volunteer vacation week. My work doesn’t matter.

My pride stings through stages: hurt, frustration, confusion.

Humility. The heavy work was for me, I realize: to understand the burdens of receiving.

Not Eve

by Iris Reinbacher

“Hi, my name is Adam, and I’m such a lonely guy!”

I’d just introduced myself to the postdoc I was supposed to work with on the database part of my thesis project. I smile uncertainly—surely, he only wants to be funny, in his awkward, nerdy kind of way.

“How old are you?” he asks.

“Twenty-eight.”

“Aahh!” he points a finger at me. “Your biological clock is ticking!”

We’ll work together for the next two and a half years. We’ll become colleagues. But we’ll never talk about the day we met, or mention ticking clocks again.

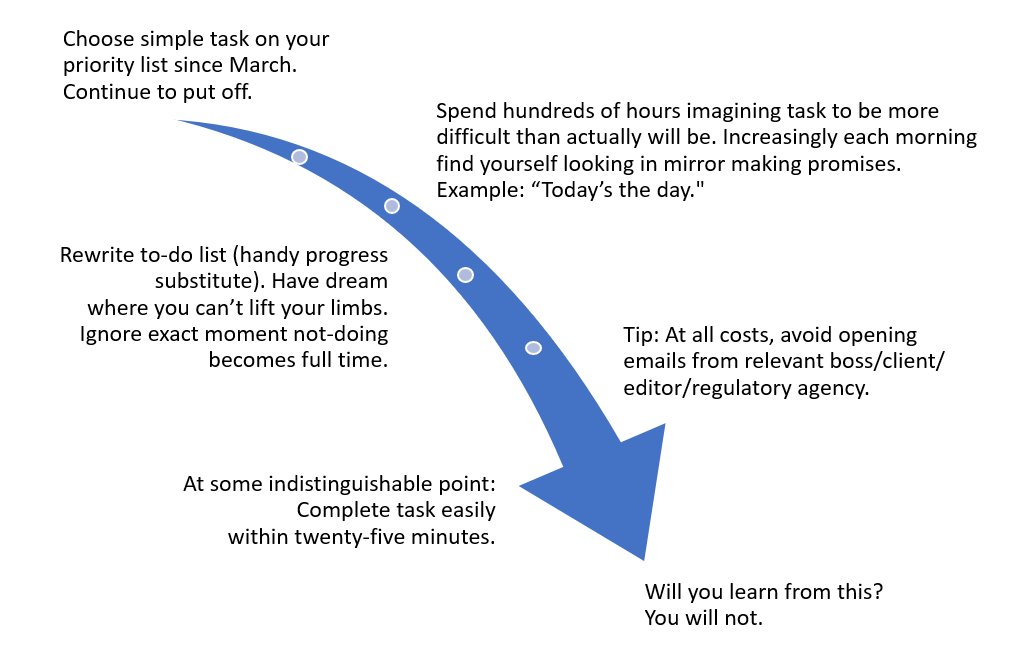

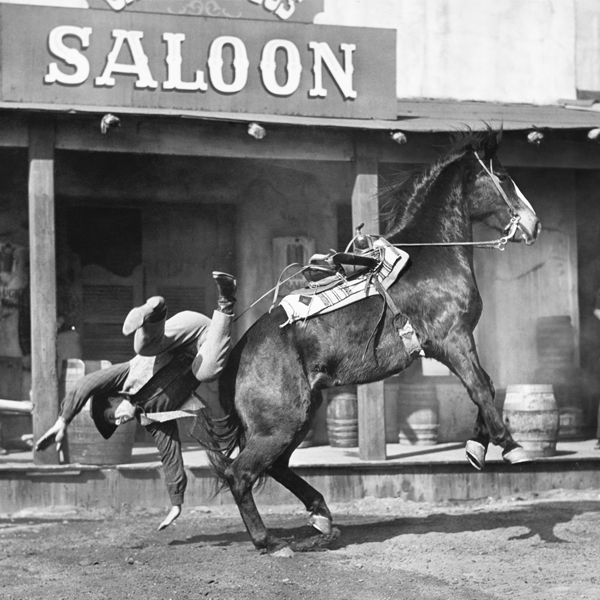

That Time I Thought I Knew Better

by D.A. Stern

Bantam Books, 1983, New York City, most of the company away at a conference. A young editor, I was on duty to receive the foreword to Lonesome Gods, one of Bantam’s next big books. Written by Louis—100 published novels, 320 million copies in print—L’Amour.

The fax came in.

I decided it wasn’t proper English. I would clean it up.

It got worse. I worked harder. It got much worse. I called my boss, the legendary Irwyn Applebaum.

“Dave, what the f*** are you doing? Just leave it alone.”

And I did. I left it Louis L’Amour.

About the Writers

Michele Wick, PhD writes about the confluence of art, science, the humanities and climate change. She is a Lecturer in Psychology at Smith College. You can read her blog Anthropocene Mind at Psychology Today.

Gerard Sarnat, MD is a physician and award-winning poet who has published four collections. His work has appeared in Main Street Rag, New Delta Review, Texas Review, Brooklyn Review, LA Review, San Francisco Magazine, and The New York Times.

Wren Bellavance-Grace is a writer based in western Massachusetts currently finding the non-working experience of sabbatical deeply disquieting. She holds an MFA in Creative Nonfiction from Bay Path University.

Iris Reinbacher is a writer and Austrian computer scientist turned entrepreneur. She has lived in six countries in Europe and Asia before settling down in Kyoto, Japan.

D.A. Stern is the author of more than two dozen works of fiction and non-fiction, including The New York Times bestsellers Crosley and The Blair Witch Project Dossier, and the acclaimed epistolary novel Shadows In The Asylum.

The Quick Work series is curated by Multiplicity Contributing Editor, Kate Whouley.

Submissions to Quick Work (100 words or fewer) are currently closed, but we welcome stories (up to 5,000 words) for the Fall issue of Multiplicity Magazine: At Work. Magazine submissions close on September 25, 2020. More details here.