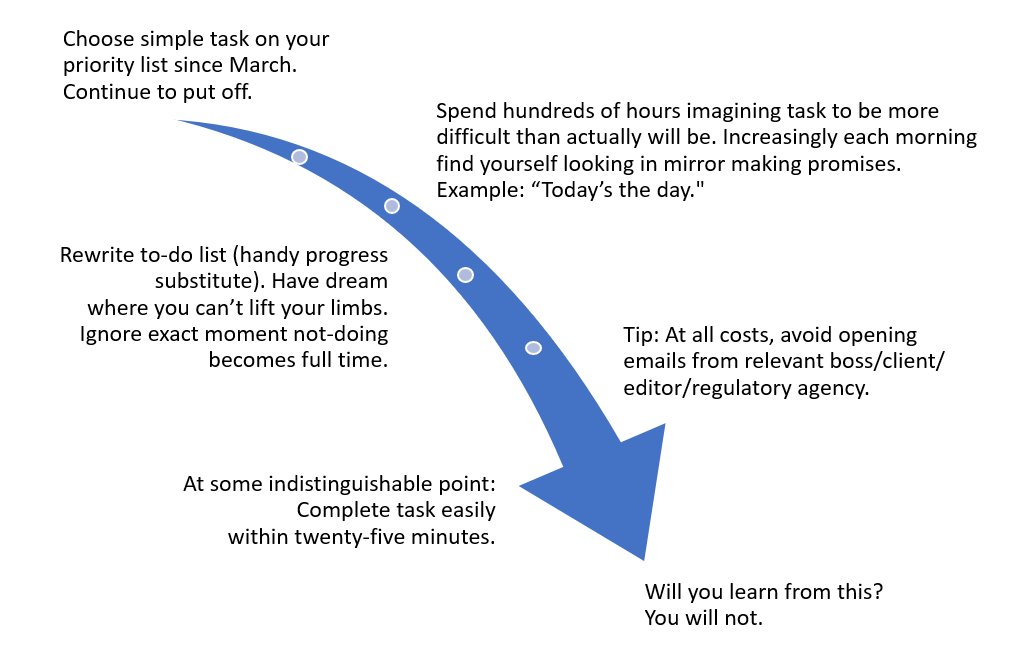

With Bells on My Boots

With Bells on My Boots

A Disabled Woman’s Relationship with Style and Beauty

By Dana Robbins

I was 23 when I had the stroke. It paralyzed my left side and left me mourning the breezy, beautiful young woman I had been. Even after several years of intensive physical therapy, my left foot pronated and dragged. My left arm sometimes froze with a bend at the elbow. With the left side of my face paralyzed, my smile is still slightly askew.

As a young girl and throughout my early twenties, people commented on how pretty I was with my long dark hair, porcelain skin, large green eyes and petite hourglass figure. In my family, the women were expected to be beautiful. My grandmother, an old school Russian beauty, told us that a man only need be one step above a monkey but a woman must be beautiful. Beauty defined my self-worth. After the stroke, people looked at me with pity and shock. I felt deep shame seeing myself in a mirror.

A few days before the stroke, I was in an Upper East Side boutique looking at a beautiful pair of green slingback shoes. They were costly, so I passed on them. Being only five foot two, I loved the lift and line a good pair of heels could give me. As a young professional, I felt more polished in heels. I remembered the slingbacks as I lay in my hospital bed. Life is short. I shouldn’t have denied myself. When I told my mother the story, she left my bedside and returned with the shoes. I rolled right out of the left shoe. I’d never wear high heels again.

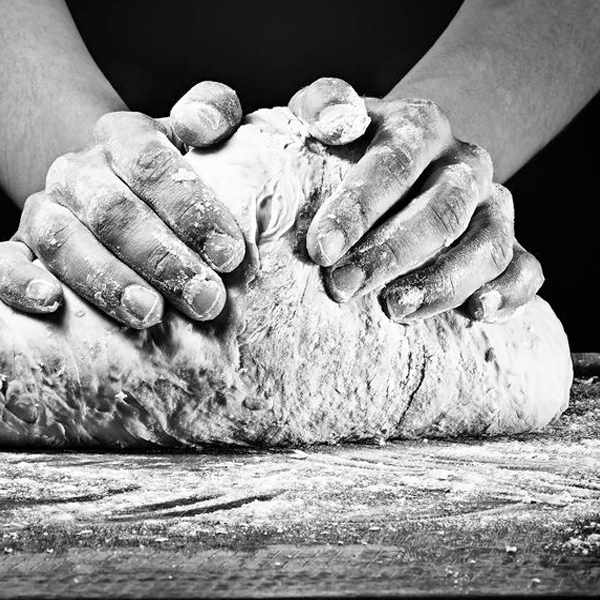

Shoes are a complicated proposition. I need a built-up, wide-footbed shoe with strong support for my left ankle. I also wear orthotics. As a child in the sixties, I was forced to wear heavy shoes that were supposedly good for the development of my feet. I hated the heavy clomp-clomp when I walked. After the stroke, I felt like those dreaded shoes returned to torment me. I spent years in denial, buying heels and fancy shoes I couldn’t wear. Like Cinderella, I believed that finding the magic shoes would make me whole. After developing pain in my left knee from my gait in my fifties. I was forced to become more realistic.

After my stroke, I had to relearn getting dressed, how to ease my paralyzed arm into a sleeve first and putting on my bra over my head. Shirts and jackets slide down my left shoulder. Décolletage, or even a normal open neck, slips off and I look disheveled. Zippers on jackets are impossible with one hand. I can’t tie my shoes or buckle a belt. I need Velcro or buttons, but neither hold well. I can’t get my left hand into a glove or mitten. During winter, I wear fingerless gloves. They’re easier to put on, but not warm.

Wearing pantyhose is another ordeal. Years ago, working as a lawyer, I wore skirted suits with stockings nearly every day, resulting in piles of ripped pantyhose. Struggling to pull them up, I’d pull too hard, and another pair would bite the dust. Now that I’m in my sixties and retired, nobody would blame me if I only wore sweatpants and sneakers. I’m just not ready to surrender beauty.

Long ago, I promised myself that if people are going to stare at me, I will be wearing the nicest clothing. Fortunately, designers are becoming aware of fashion needs for disabled women, featuring clothing easier to get into. The Cerebral Palsy Foundation even sponsors a design for a disability fashion show. “Shop until you drop” is a reality for me because trying on clothes is tiring and I break into a sweat inside the dressing room. If I don’t have anybody with me, I gravitate to small stores where the staff is helpful.

Grooming is taxing. Since I can’t cut or file my nails, I get regular manicures. If my left hand isn’t carefully positioned palm down, my thumb pulls inward and my hand involuntarily forms a fist, smudging the polish. Often, a manicurist who doesn’t understand grabs my hand off the table and says “relax.” My hand does the opposite, curling like a starfish poked with a stick, frustrating both of us.

I can’t do much to style my hair. Most hairdryers require two hands, one for the dryer, one for the brush. I keep my hair medium short and my excellent hairdresser cuts to my natural wave. All I do is shampoo it. My husband would love for my hair to be longer but I wouldn’t be able to put it up on a hot day.

In our society, disability is shameful and maintaining my appearance is important for my self-esteem. In this, my role model and inspiration is disabled artist, Frida Kahlo. Her iconic style, derived from traditional Mexican garb, was not only an expression of ethnic pride but a way of working around her disability. It wouldn’t be fair to say she “concealed” it. Many of her paintings depict her naked. To disguise the unevenness of her legs caused by childhood polio, Kahlo designed red suede boots with a built-up platform. After a bus accident damaged her spine and pelvis, she underwent multiple surgeries. She then had to wear steel corsets. Her long full skirts covered her withered leg. Loose blouses and ruanas flowed over the corsets. Her elaborate jewelry and coiffure drew attention upward to her striking face.

Many years after her death, Kahlo’s unique style is admired worldwide and is enshrined in the Frida Kahlo House Museum in Mexico City. There, I once stood before an embroidered red suede boot, which she once wore on her right foot. The most captivating details were the two small jingle bells fastened to the laces. Instead of the uneven clomp-clomp, there was the pleasing sound of bells.

Kahlo said, “Viva la Vida. Live Life.” Like Frida Kahlo, whatever my physical limitations, I will dress in beautiful outfits, and metaphorically, will have bells on my boots.

About the Writer:

After a long career as a lawyer, Dana Robbins earned an MFA in creative writing from the Stonecoast program at the University of Southern Maine. She is the author of two published books of poetry, The Left Side of My Life and After the Parade (both published by Moon Pie Press, Maine ). Her poems and essays have appeared in numerous publications.

.